Choosing between accuracy and entertainment wasn’t created

by the invention of the motion picture camera. Shakespeare had this problem

when he was writing his plays. He knew his audience, the Tudors, and he wasn’t

against twisting history to make their ancestors look good. His desire to

entertain often overcame whatever desire he may have had for historical

accuracy. Poor Richard III’s reputation suffered for it, and will probably

never recover, no matter what archeologists find under that parking lot in Leicester

(read more about that here).

Choosing between accuracy and entertainment wasn’t created

by the invention of the motion picture camera. Shakespeare had this problem

when he was writing his plays. He knew his audience, the Tudors, and he wasn’t

against twisting history to make their ancestors look good. His desire to

entertain often overcame whatever desire he may have had for historical

accuracy. Poor Richard III’s reputation suffered for it, and will probably

never recover, no matter what archeologists find under that parking lot in Leicester

(read more about that here). Sometimes these tropes can work in a writer’s favor by

allowing us to establish a setting with just a few words. For example, if I say

Colosseum, you instantly imagine a massive arena in ancient Rome. If I say Vikings

you automatically think of warriors wearing horned helmets when in reality,

there is very little evidence that they actually wore them. And there’s the

rub. As historical fiction writers, when do we write to be accurate and when do

we write to fulfill reader expectations?

Sometimes these tropes can work in a writer’s favor by

allowing us to establish a setting with just a few words. For example, if I say

Colosseum, you instantly imagine a massive arena in ancient Rome. If I say Vikings

you automatically think of warriors wearing horned helmets when in reality,

there is very little evidence that they actually wore them. And there’s the

rub. As historical fiction writers, when do we write to be accurate and when do

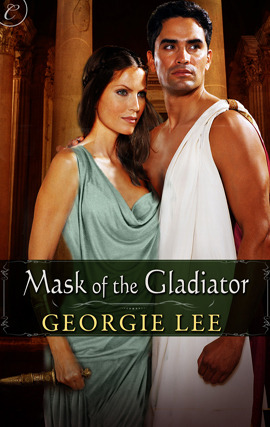

we write to fulfill reader expectations? I faced this challenge in an early draft of my ancient Rome

novella, Mask of the Gladiator after

my sister reminded me that the capital “C” Colosseum wasn’t built until 30

years after my story took place. This proved a bit of a conundrum. After all,

I knew readers would expect to read about gladiators fighting to the death in

an impressive arena and such a venue also added to the drama of my

opening. So, after doing some research

to back up my decision, I did a quick find and replace and set the opening in an

unnamed lowercase “c” colosseum. It was historically accurate since there were

large arenas in use by gladiators during Caligula’s reign. Also, by using the

word colosseum, I instantly created a picture in reader’s minds, even if it may

not be the exact, historically accurate one.

I faced this challenge in an early draft of my ancient Rome

novella, Mask of the Gladiator after

my sister reminded me that the capital “C” Colosseum wasn’t built until 30

years after my story took place. This proved a bit of a conundrum. After all,

I knew readers would expect to read about gladiators fighting to the death in

an impressive arena and such a venue also added to the drama of my

opening. So, after doing some research

to back up my decision, I did a quick find and replace and set the opening in an

unnamed lowercase “c” colosseum. It was historically accurate since there were

large arenas in use by gladiators during Caligula’s reign. Also, by using the

word colosseum, I instantly created a picture in reader’s minds, even if it may

not be the exact, historically accurate one.

When to be accurate and when to write to readers’ expectations

is a hard call, but in the end, I think the decision comes down to the story. As

writers, when do you make the call? As readers, how accurate do you want your

history, or do you actually expect certain tropes?

No comments:

Post a Comment